What is Modernism?

Arising in the early twentieth century, Modernism was a new wave of thinking, creating and performing. It is very difficult to pin point as one specific ideology and rather consists of several states of mind springing up around Europe. Ranging from script based educational pieces to non linear fragmented dances, modernism bought the voice of antagonism to performance.

A performance style did not unite these artists but several intertwining vexes that are arguably as topical today as they were know. At a similar time industrialisation was sweeping across the world after Britain’s success and expansion. This provoked concerns by many resulting in social unrest and a sense of self determination by those under the control by politicians and their politics. Almost hand in hand with politics and machinery is war. War is a key feature of modernist creativity and is something that potentially allows modernist to live on today.

Yang Shaobin

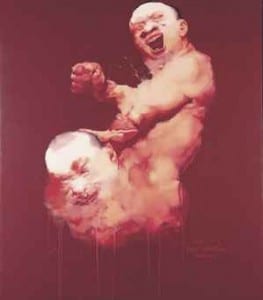

This is a painting by Yan Shaobin.

Using a canvas and a few oil paints he has depicted the pain and torment of oppression in China. As you can see in the painting it is not just subject matter that Shaobin uses as the modernists would. He shows mutilated bodies in a way to represent distortion and troubled souls.

Below is further proof that Shaobin is a modern day modernist. This installation is called Wound. Shaobin states ‘I’m still very much taken with the uniqueness of people. If I’m in the hospital I like looking at those people on the brink of death, with their bloodless nails and wound’ (Giuffardi, 2004). His work see the beauty in those in pain and in those who are suffering and draws attention to them.

Franz Kafka – Metamorphosis

Kafka’s novel tells the story of a man, Gregor Samsa, who ‘awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself changed into a monstrous cockroach in his bed’ (Kafka, 2007, p. 87). The novel has had many mutilations itself of stage, screen and art, similar to the mutilation Kafka puts poor Gregor through. It’s open meaning has many interpretations such as the anxiety that a man of his profession faces in life. Whatever the adaptation is it always depicts a body that has been mutilated like the work of a modernist. furthermore, it certainly comments on an oppressive life that has been served to Gregor.

How it affects me…

Modernism is about the here and now and social consciousness. I believe that my plays are very contemporary in terms of writing style but also in terms of subject matter. I am exploring human emotion in the modern age not that of a 1920’s revolt, but still a society fuelling rebellion, outcry and war. The obscure techniques that some modernists use are interesting to me as i do not want audience who see my play, or those who read it, to fully understand what they are seeing. But like the modernist I have a goal. I want people to take hat they can from my play and then apply it to their lives. It may not result in the self realisation and revolution, which may have spawned from an Agit-Prop pop up performance, though as sense of realisation or reflection may occur.

So I thank the modernists for being brave and standing up, and for letting me continue to do so.

Works Cited

Giuffardi, M (2004) Interview with Yang Shaobin. [online] Beijing: Yang Shaobin. Available from: http://www.yang-shaobin.com/eng/htm/pinglun/2004-p/2004-1_main.htm [Accessed 2 December 2014].

Kafka, F. (2007) Metamorphosis and Other Stories. London: Penguin

As Paul Fry states ‘without doubt one of the most murky concepts to which we’ve been exposed in the past twenty or thirty years’. As a result, composing a definition of postmodernism is almost impossible as each different art form has its own measures for defining it. This is why is cannot be seen as a movement as there is no unified direction or intention of the postmodern artists and rather a further sense of the individual. Philip Auslander attempts to define a postmodernist as someone whose work possesses ‘stylistic features that align them with postmodernism as a feeling, an episteme, rather than a chronologically defined moment’ (2004, p.98). Auslander then continues to discuss postmodernism’s effect on art. He states ‘Michael Benamou… identifies performance as “the unifying code of the postmodern”‘ (2004, p.99).

As Paul Fry states ‘without doubt one of the most murky concepts to which we’ve been exposed in the past twenty or thirty years’. As a result, composing a definition of postmodernism is almost impossible as each different art form has its own measures for defining it. This is why is cannot be seen as a movement as there is no unified direction or intention of the postmodern artists and rather a further sense of the individual. Philip Auslander attempts to define a postmodernist as someone whose work possesses ‘stylistic features that align them with postmodernism as a feeling, an episteme, rather than a chronologically defined moment’ (2004, p.98). Auslander then continues to discuss postmodernism’s effect on art. He states ‘Michael Benamou… identifies performance as “the unifying code of the postmodern”‘ (2004, p.99).